Helena and Stefania Podgórska, ca 1942

Stefania Podgórska Burzminski

For two years During World War II in Nazi-occupied Poland, teenaged Catholic girl Stefania Podgórska and her younger sister Helena provided secret refuge in the attic of their home for thirteen Jews, rescuing them from near certain death at the hands of the Nazis.

The story begins in early 1939, in Przemyśl – a city in southeastern Poland, near the border of what is currently Ukraine. Stefania, then a young teenager, was working at a small general store owned by a Jewish family named the Diamants. It was there that Stefania fell in love with Izio, one of five Diamant children. While a relationship between a Catholic girl and a Jewish boy was unusual at the time, the Diamants were not particularly traditional, and they did not object.

That fall, war came to Przemyśl. The Polish army held off Nazi advances for just three days before the Eastern part of the city fell under Nazi control. When the battle ended, German soldiers and police carried out a systematic three-day massacre that claimed the lives of more than 500 Jews, while thousands more were taken from their homes and deported into the city’s Soviet occupied western territory, where the Podgórska and Diamant families resided in relative safety.

By 1941, the Nazis had taken the entirety of Przemyśl – and both families were torn apart. Stefania’s already widowed mother and seven siblings were sent to Germany to work as slave laborers for the Nazis, while the Diamants were imprisoned in the newly walled-off section of town that would soon come to be known as the ghetto.

Nazi atrocities accelerated. In July of 1942, Mr. and Mrs. Diamant were sent to Belzec death camp, where they perished in the gas chambers almost immediately after stepping off the train. Izio – Stefania’s young love – was taken to Janowska labor camp, where he was eventually killed. News of Izio’s death devastated Stefania, who was living – at the Diamant’s request – in the apartment the family had vacated when they were sent to the ghetto. Stefania’s only company was her eight-year old sister Helena, who had been left with neighbors when the girls’ mother was taken to Germany.

Later that year, two more Diamant children, Chaim and Max, found themselves, like their late parents, in a cattle car on the train to Bełżec. The younger, Max, had hidden a pair of pliers in his coat, which he used to cut the four strands of barbed wire that guarded one of the car’s small windows. He urged his brother Chaim to jump with him. But when the train slowed down to round a bend, it was only Max who jumped. He would never see his brother again.

The fall left Max badly beaten and bruised, but not broken. He found the strength to walk five miles to Lipowica, a hilltop forest. It was there that he rested, briefly, before traversing the final four miles to his parents’ apartment, where he a shocked and elated Stefania opened the door. He asked her to let him stay for just one night. She did, and the next morning she refused to let him leave. As the Nazis continued to empty the ghetto by deporting its occupants to the death camps, Stefania and Max grew determined to bring Max’s only remaining family, a brother who still remained in the ghetto with his fiancée, to safety.

As a young child, Helena was able to move about while avoiding unwanted attention more freely than the elder Stefania. She would play near the ghetto fence, secretly waiting for the opportunity to pass a letter containing instructions for Max’s brother. Working in this way, the girls were able to rescue the couple. Later, they assisted several more escapees, and it was not long before the apartment proved to be too small and too dangerous a place for all of them to stay. Stefania found and rented a small house, located at 3 Tatarska Street, about half a mile from their previous residence. The house had no electricity or running water, but it did have a good sized attic. Under cover of night, Stefania and Helena scuttled Max and the others to the new residence. Max built a false wall in the attic using scrap wood that Stefania and Helena had salvaged from bombed-out buildings. Unfortunately, there was no time to do anything about the rats that also called the attic home.

Left Photo: ca 1985 shows the rear of 3 Tatarska Street where Fusia and Helena lived. Hand-pump for well water in foreground. The two small square windows near the roof are in the attic. The right square window in the attic is where the bunker was that hid 13 people. Right Photo: Also from 1985 shows the front of 3 Tatarska Street which was occupied by neighbors during the war.

With more space available, the sisters continued their efforts to rescue people from the ghetto.

One afternoon, as Helena prepared to pass a letter near the fence, a bystander alerted Nazi guard. The guard ordered her to stop. The act of passing such a note was punishable by death, even for a child. Moreover, the note, still in her hand, read “Tatarska 3” – the address of the house that was already sheltering close to a dozen Jews, all of whom would surely perish if she were captured.

Helena ran.

The SS guard gave chase, and eventually caught her. A struggle ensued as the guard beat and kicked young Helena. Many years later, Helena recalled the encounter in an interview. “I have no idea how it happened,” she said. “I defended myself, but I was just a child. So I bit him in the leg…And I must have bitten him hard because he let go of me and grabbed his leg. So I ran away. I ran to my house. I remember how I cried.” Still holding the note, and afraid the guard was going to come after her, she swallowed it. “I was in a terrible shock,” she said. But what could I do?” It was the narrowest of escapes.

Several months later, thirteen Jews ranging in age from ten to fifty were living in the Podgórska’s small attic. It was terribly cold in the winter, and oppressively hot in the summer. Their bathroom was a bucket that had to be emptied daily into the outhouse. They relied on the girls to feed them. Bathing was a challenge. They had to be fed. They had no medical care. They could not leave. If the girls were to continue to support everyone, they would need income. But even the elder Stefania was still too young, legally, to work. With the help of a friend, she obtained false papers, which allowed her to get a job making screws and bolts at a local manufacturing plant, and earn the money needed for food and supplies. For her part, eight-year old Helena continued to carry out the laborious and dangerous tasks needed to help them all survive. She carried water from the well, emptied the bucket in the outhouse, and shopped discretely for food at open-air markets.

One day, an SS officer knocked on the door. He demanded that all occupants vacate the home immediately, explaining that the Nazis had commandeered a municipal building across the street from Tatarska 3, converted it into a military hospital, and would need the house to provide lodging for hospital staff. The girls were warned that they had two hours to leave, after which time they would be shot.

Panic ensued.

The thirteen Jews who had now been hidden in the attic for many months begged the girls to flee, crying out that they had done enough and should save themselves. But the girls refused to leave. At the end of two hours, there was a knock on the door. This time, it was a different SS guard. Casually, he informed the girls it was good they had not moved out. He said they would not need the entire house after all – only one room. Only hours later, two German nurses moved into the small bedroom directly below the attic where the thirteen Jews were hiding.

This living situation went on for several months. The nurses schedule varied, and it was impossible to predict when they would come and go. They frequently hosted the Nazi soldiers they dated for overnight stays. One night, the nurses complained of noises in the attic, and sent one of the soldiers up to investigate. From the kitchen table, the sisters watched in terror, helpless, as he climbed the ladder. It seemed that all would soon be lost.

And then, the soldier climbed back down. “Rats,” he explained. “Filthy Poles.”

3 Tatarska Street on left and the building that was the German Army hospital on right.

On July 23, 1944, Soviet planes bombed Nazi targets in Przemyśl. Four days later – on the second anniversary of the Nazi’s first major deportation of Jews to the Belzec death camp – the Russians captured the city. By the time the Nazis were pushed out, only 300 of the approximately 16,000 Jews who had lived in the Przemyśl area had survived the war.

The Soviets went door-to-door as they secured the city, and it was not long before a Soviet soldier burst through the door of Tatarska 3. Stefania asked the soldier if the Nazis were gone. He said yes. At that moment, the hungry, terrified, and traumatized group that had been hidden in the attic for nearly two years cautiously came down the stairs. Startled, the Soviet soldier raised his rifle. Stefania shouted that the group was not a threat, explaining that they were Jews, hiding from the Nazis. The soldier revealed that he too was a Jew.

Incredibly, the nightmare was over, and everyone who lived at Tatarska 3 had survived.

Shortly after the war, Stefania married Max, the first to come to her after bravely leaping from the train to Belzec two years prior. He had changed his name to Josef, the name of a dead Polish man whose identity he assumed to protect himself from the pogroms, or riotous hordes of people who were still hunting Jews across Eastern Europe. Stefania would often joke, “He asked to stay for only one night and he stayed over fifty years”. Speaking about Stefania, Max would say “She gave me…life, I owe her mine.” In 1961, the couple immigrated to the United States. When a fire in an apartment building near their home in Boston left dozens homeless, Stefania and Max welcomed nine strangers into their home, and cared for them for several weeks.

Remaining in Poland, Helena endured much after the war. She became a physician, but the oppression of the Nazis was replaced by the oppression of communism, and Helena was shunned by some who knew she had rescued Jews. Today her mind remains sharp, but the toll on her body from all the physical labor she endured as a child is debilitating in old age.

When asked why the sisters risked everything to protect others, Stefania would usually explain only that she “had to help,” because “we are all human beings.” But this selflessness also came with a price. In the late 1970s, Stefania began to display signs of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). She suffered from severe insomnia, frequent flashbacks, which almost constantly put her “upstairs in the bunker,” uncontrollable crying, bouts of depression, and eventually, dementia.

Despite the gravity of this terrible disease, it set Stefania free. She forgot the past, and for the first time in her life, her mind was at ease. She died in 2018, singing Polish songs and emanating the warmth and joy of a person whose youth had been taken from her, but whose life and spirit were resilient beyond imagination.

Fusia returns to the attic in 1985, for the first time since the war ended. Visible on the left wall is where the false wall once rested against and exposed a vertical timber. The window on the right is where one of the hidden would always keep watch on over the courtyard for unexpected visitors.

Many of those rescued by Fusia came together to recognize her heroism and in 1979, she was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Israel. Fusia’s story has been memorialized in a television movie titled “Hidden in Silence,” in a documentary titled “The Other Side of Faith,” in a segment on the television show “In the Name of Love,“ and in multiple interviews for newspapers, television news, and various Holocaust archives. She was a featured guest on “Oprah,” spoke at the dedication of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., in which she is featured at the Rescuers exhibit, and was recognized by Women’s Day USA in Los Angeles.

A fictionalized version of Fusia’s story is in the young adult novel titled “The Light in Hidden Places” by Sharon Cameron, published by Scholastic Press. An audiobook version is passionately voiced by Beata Pozniak Daniels, an award-winning Polish-American actress who founded Women’s Day USA, honored Fusia as an inspirational woman, and was Fusia’s friend.

3 Tatarska Street in 2019 during renovations to become a museum.

Tatarska 3, the house in Poland where Fusia and Helena hid thirteen people is currently being converted into a living museum by a compassionate businessman in Przemyśl to memorialize the heroism of these two young ladies.

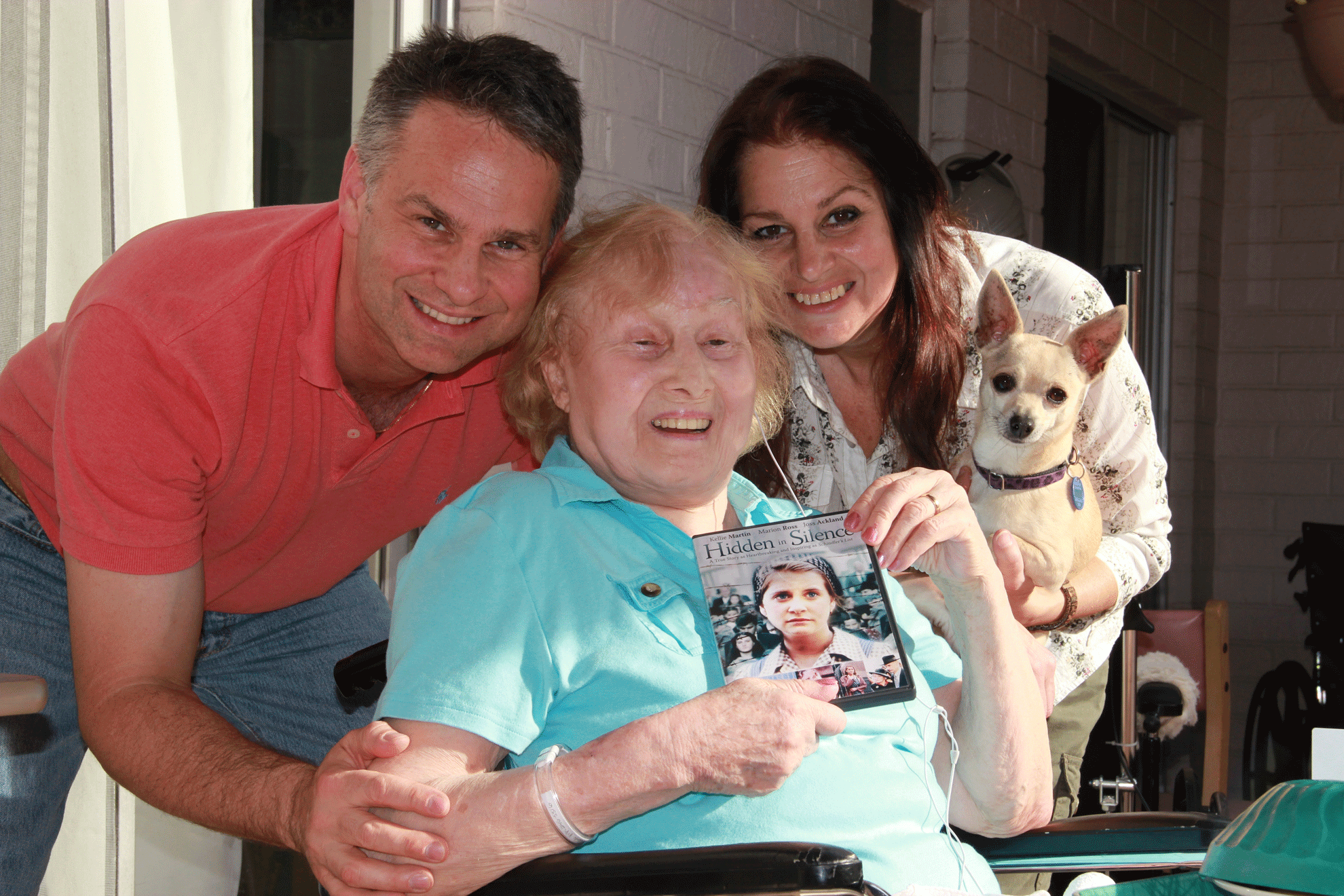

Fusia and Joe had two children, Ed and Krystyna, who are the stewards of their parents’ story. Pictured are Ed Burzminski, Joe Burzminski (Max Diamant), Stefania “Fusia” Podgorska Burzminski and Krystyna in 2002.

Fusia and Joe had two children, Ed and Krystyna, who are the stewards of their parents’ story.

Fusia died in September 2018 and her humble yet extraordinary life continues to touch and inspire.

The Rescued

Some items require free registration to view.

The illustration above was made by Josef Burzminski (nee Max Diamant) in the 1980s depicting Stefania and Helena as guardian angels, Stefania protecting the 10 adults and Helena protecting the 3 children.

Max Diamant (Josef Burzminski)

Max Diamant was Henryk Diamant's older brother. Max was #1 to arrive to Fusia. Max was the "president" of the Tatarska...

Dziusia Schillinger

Dziusia Schillinger was daughter of Wilhelm Schillinger. Dziusia was 12 years old when she came to Tatarska 3....

Henryk Diamant

Henryk Diamant was Max's younger brother. Henek was Danuta Karfiol's fiance.

Danuta Karfiol

Danuta was Henek Diamant's fiancee.

Wilhelm “Wili” Schillinger

Dziusia Schillinger's father. Max Diamant worked for Doktor Schillinger as a dental technician and a junior dentist....

Sala Hirsch

Married to Monek Hirsch.

Doctor Leon Hirsch

Siunek Hirsch's father. Monek Hirsch's cousin. Sala Hirsch's cousin by marriage. Doktor Hirsch was the financier of...

Mojzes “Monek” Hirsz

Doktor Hirsch's (Hirsz) cousin. Sala Hirsch's (Hirsz) husband.

Siunek Hirsch

Doktor Hirsch's son. He and Max got along well in the attic. Siunek was the "vice-president".

Malwina Zimmerman

Malwina Zimmerman is the mother of Cesia and Janek.

Teodora Cesia Zimmerman

Teodora "Cesia" Zimmerman was the daughter of Malwina Zimmerman and brother of Janek Zimmerman.

Janek Zimmerman

Janek Zimmerman was the son of Malwina Zimmerman and brother of Cesia Zimmerman.

Jakob “Janek” Dorlich

Janek was Fusia's postman. He was #13, the last to arrive.

Free Media Archives

Some items require free registration to view.

Interview – WBZ-TV4 Boston

Living in Boston in 1993, Stefi and Joe were interviewed by local television station WBZ-TV4 prior to their coverage...

Stefania Burzminski On Being A Rescuer

From the USC Shoah Foundation Stefania Podgorska Burzminski appears at the end of the testimony of her husband, Josef...

Women’s Day USA

In 1995, Stefi was recognized in Los Angeles by Women's Day USA and its founder Beata Pozniak, a Polish born screen...

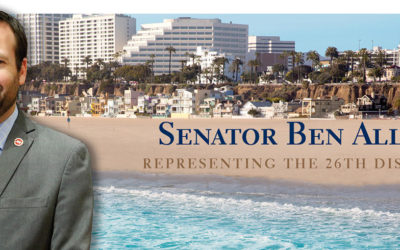

Senator Ben Allen’s Recognition

Read aloud at Stefi's funeral, this letter of recognition was presented to Stefi from California State Senator Ben...

Yad Vashem

In 1979, Fusia was honored with a "Medal of the Just" by Yad Vashem after several of the Rescued petitioned the...

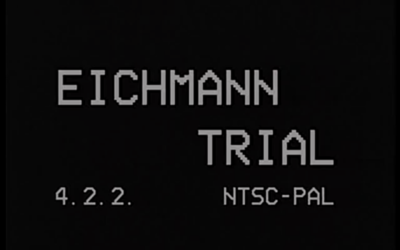

Eichmann Trial – Dr. Josef Burzminski Testimony

In 1961, Stefi and Joe lived in Tel Aviv Israel and Joe provided testimony at the trial of the Nazi...

Member Archives

Stefania’s Choice Reader’s Digest Article

An article in the August, 1994 edition of Reader's Digest titled "Stefania's Choice". Reproduced with...

The Other Side of Faith

Click here to see the film in its entirety."The Other Side of Faith" is a documentary produced by Mr. Sy Rotter about...

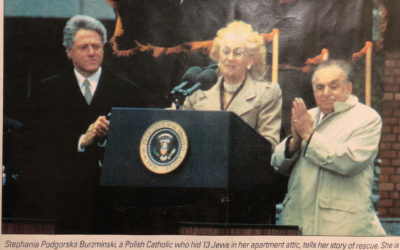

US Holocaust Memorial Museum Dedication

Fusia was asked to speak at the opening dedication ceremony of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum...

In the Name of Love

Ms. Susan Petit, at the time the publisher of Los Angeles Lawyer magazine, a legal publication of the Los...

Oral History – US Holocaust Museum

Stefi provides her oral history in 1989 to the United States Holocaust Museum. This is a series of three long,...

Interview with Polish Reporter

At the United States Holocaust Memorial Dedication in Washington DC in 1993, Stefi and Joe were interviewed for Polish...